Ivory Gull!

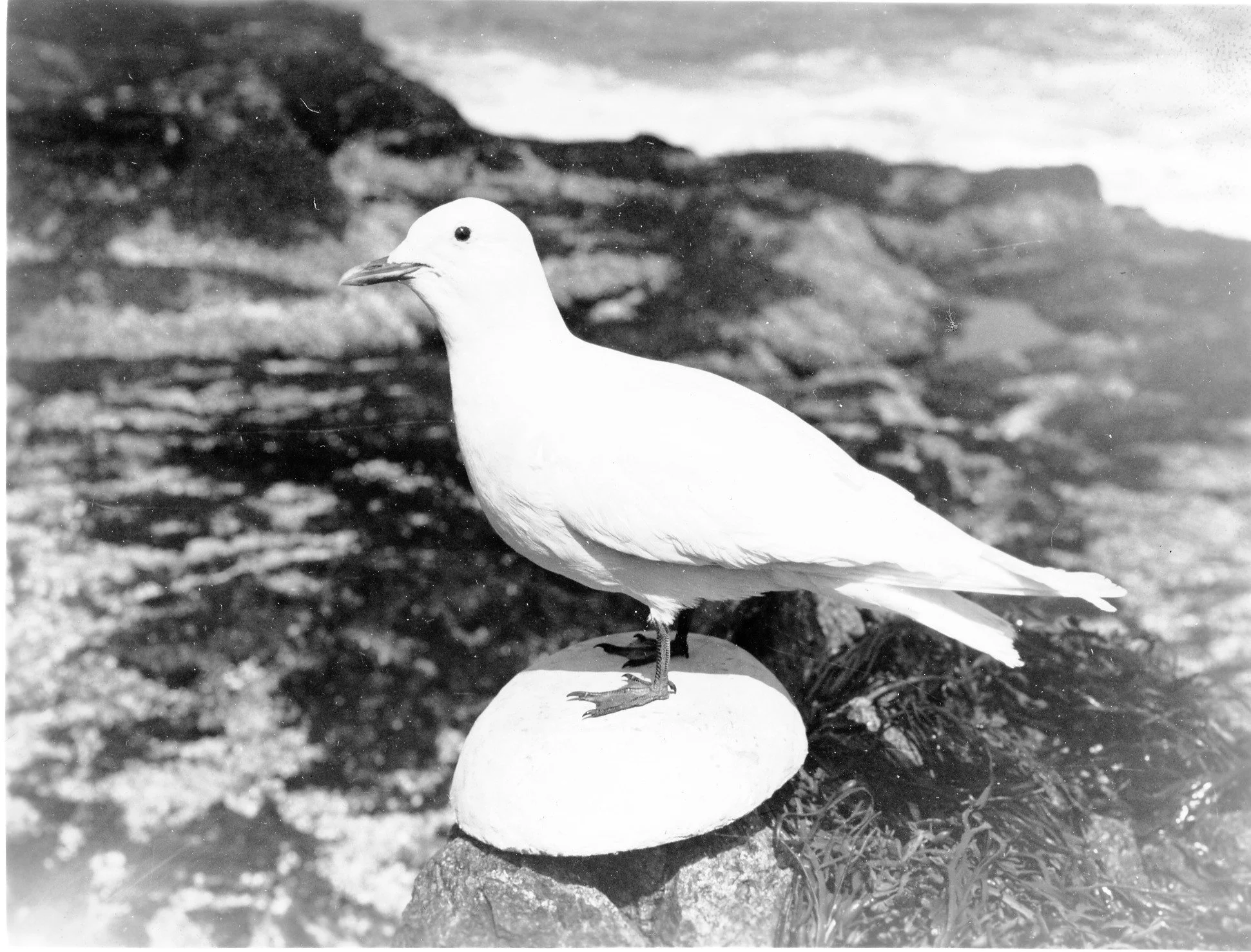

Ivory Gull taxidermied mount. Courtesy of the National Park Service, Acadia National Park.

“Ivory Gull (Pagophila alba) Adult shot at Southwest Harbor, February 10, 1940, now in collection of the Museum of Acadia National Park, Bar Harbor.” Those 26 words comprise the complete Ivory Gull entry in Carroll Tyson’s and James Bond’s 1940 book, “Birds of Mount Desert Island, Acadia National Park, Maine.” For decades, they have gnawed at me.

Since my youth, I have had an affinity for everything related to extreme latitudes. I read tomes on polar exploration by the likes of Fridtjof Nansen and the ill-fated Sir John Franklin expedition. Inuit technology for surviving Arctic environments fascinates me. I long to see Narwhals, Polar Bears, and Musk Ox. And, of course, Ivory Gulls.

So, what makes an Ivory Gull special? They are “ice gulls,” highly specialized Arctic seabirds dependent on sea ice for feeding (they often scavenge Polar Bear kills) and roosting (they like to hang out on ice floes). They nest on Arctic cliffs, sometimes as much as 40 miles from the sea, requiring long daily flights to their marine feeding grounds. And they rarely venture far from the Arctic. According to the Maine Bird Records Committee, only six have been adequately documented as occurring in the entire state.

During the halcyon days of the 1990s, a group of friends and I came to Acadia National Park for a week of hiking, climbing, and kayaking. Approaching Ellsworth, we spied Big Chicken Barn. We just had to stop to browse their extensive used book collection. It was there that I stumbled upon Tyson and Bond’s small, slightly tattered, yellow-covered book. That evening, around our Blackwoods Campground campfire, I read the book in its entirety. Those 26 words beckoned. I might not see the Ivory Gull but I was intrigued by the fact of one appearing in Southwest Harbor long ago.

Years later, now living in Town Hill, I came across a note by Acadia National Park ranger Maurice Sullivan published in a 1940 issue of “The Auk,” the journal of the American Ornithologists’ Union, entitle “Ivory Gull from Mount Desert Island, Maine.” Sullivan relayed a telephone call from Wendell Gilley describing a “small, pure-white gull sitting on an ice-cake near a wharf.” Sullivan asked Gilley to “collect it immediately, because it is quite rare.” My interest rekindled, it was time to find me an Ivory Gull. Or, at least, a taxidermied one.

I started with the archives section of Acadia National Park. They did not know about any such taxidermy mount, nor could they find it in their collections. I was referred to the National Archives in Boston as some Acadia collections had been sent there. Another dead end. I turned to Bill Townsend, the embodiment of institutional memory for everything bird related on MDI. Word on the street was that George B. Dorr, the “Father of Acadia” and the park’s first superintendent, was a packrat and that when he passed in 1944, many items in his office were lost. Maybe this happened to the Ivory Gull.

In 2022, I was a speaker in Friends of Acadia’s “Pints for a Purpose” series at Terramor Resort. While sharing some anecdotes of our local ornithological history, I mentioned Maurice Sullivan, Wendell Gilley, and the Ivory Gull story. Afterward, FOA’s Lisa Horsch Clark said I had piqued her interest and she was going to investigate further.

Every lead turned up a dead end. Several years went by. Lisa would occasionally check in with me whether I had any news on the bird. Nada.

So, imagine my surprise when just last week, I received an email from Acadia National Park’s curator, Marie Yarborough, stating she had finally tracked down the Ivory Gull! It turns out the bird was in Augusta with the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife.

Ivory Gull refound! Courtesy of the National Park Service, Acadia National Park/Yarborough.

When considering the Ivory Gull, we should look at it through the lens of the era: “collecting” had long been considered the best way to document a species. This is not to make it right, but we do need to understand the way science was conducted at the time. Here was a rare bird. The accepted way of documenting was to “collect” it. So, it was “collected.” Fortunately, today, we know better.

There is scientific value to collections. They can serve as archives for research on evolution and biodiversity. For instance, analyses of DNA from live birds, when compared with museum specimens, have yielded fascinating results between contemporary birds and those “collected” before the Industrial Revolution. We are learning how human-driven environmental changes have rapidly altered bird genetics over just a few centuries. We have also found modern populations often show significantly lower genetic diversity compared to their pre-industrial ancestors. And that habitat fragmentation and population declines over the past 200 years have led to "genetic bottlenecks," making many species more vulnerable to disease and climate change.

For centuries, “collecting” specimens was de rigueur. During the 17th and 18th centuries, wealthy Europeans “collected” so-called cabinets of curiosities. Displaying these natural items was a sign of social status. Exploration and desire for scientific documentation became widespread during the 19th-century Victorian era. This was when the Smithsonian Institution and the Natural History Museum at Tring (located in London) were created. Today, these two institutions host some of the largest natural history collections in the world. They actively recruited collectors in order to amass specimens for scientific and taxonomic studies, seeing them as essential for understanding diversity.

Global conflict during World War II led to a significant reduction in “collecting” specimens. Awareness of our role in extinctions (think Passenger Pigeons, for one) also came to the fore. Post-war, the need for “collecting” was replaced by the contemporary technology of high-quality binoculars and spotting scopes, digital cameras, sound recording equipment, and now DNA analyses.

Today, the Ivory Gull taxidermied mount is back at Park Headquarters here in Bar Harbor and undergoing conservation. Now that we have the bird in hand, perhaps the Maine Bird Records Committee will finally have the documentation it needs to accept the Southwest Harbor Ivory Gull.